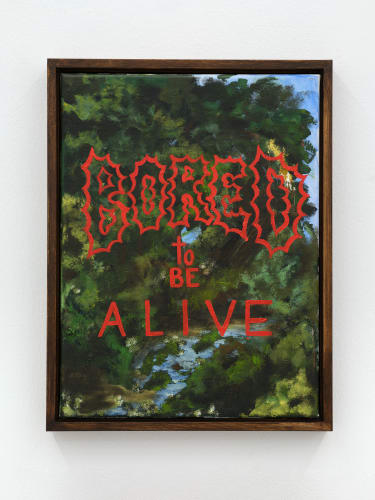

WILLEHAD EILERS

BORED TO BE ALIVE

SEPTEMBER 05 - OCTOBER 04, 2025

In his latest solo exhibition, Bored to be alive, Willehad Eilers combines painting and text to create a multi-layered exploration of emotion, pictorial conventions and the question of what "real" art is allowed to convey. The starting point for the series was an attempt to work without a plan – intuitively, calmly, without pressure. But instead of relaxation, a phase of emptiness set in, in which frustration and insight went hand in hand. "How long do I have to stare until nature finally has an effect?" says Eilers. Nature, otherwise, a symbol of retreat and relaxation, becomes a projection screen for inner turmoil.

The resulting works, which visually differ significantly from Eiler's previous oil paintings, combine idyllic landscapes with verbal intervention. Texts such as "Bored to be alive" or "Jeder kann es sehen" (Everyone can see it) overlay romantically charged depictions of nature and tip them over into the grotesque, the political, the personal. The writing does not function as a mere commentary, but as a second level of imagery – comparable to a pane of bulletproof glass that protects the motif beneath it, but at the same time distances it from the viewer.

Formal and conceptual references infuse the work: Bob Ross' meditative, kitschy landscapes, Caspar David Friedrich's interpretation of man in nature, Edvard Munch's fleshy images of nature – all are implicitly present. But they are broken up by using popular cultural references and the conscious-unconscious appropriation of the image type of so-called ‘home decoration’: lettering such as "HOME," "LIVE LOVE LAUGH," or canvases with images of nature as seen in furniture stores, whose million-fold repeated aesthetics have always fascinated Eilers. This explicit visual language, often dismissed as 'IKEA art', becomes a Trojan horse here: its pleasing surface serves as a vehicle for existential, political and emotional depths.

A friction arises between painterly gesture and linguistic expression, which charges the work. Text and image do not stand in an illustrative relationship to one another – they fertilise each other. As is almost always the case in Eiler's work, it is about tone and atmosphere rather than technical virtuosity. It is precisely imperfection – trembling lines, unfinished surfaces, painterly breaks – that becomes an artistic statement here, as it did in his black-and-white drawings at the beginning of his painting career. In this age of artificial perfection, error is increasingly becoming the signature of humanity, according to Eilers.

Thematically, the current works expose socially relevant areas: war, exclusion, violence, sexism, excessive self-expression of the individual. Works such as "Wir haben es gewusst" (We knew it) or "Love Family Hate Enemy" do not address horror in a didactic manner, but allow it to settle symbolically – for example, as pus-filled pimples in a filthy coniferous forest or as a pink gorge under a blood-soaked sky. The phrase "Love Family Hate Enemy," for example, exposes the binary thinking that often builds community on exclusion. The title "Wir haben es gewusst" (We knew it) also refers to collective responsibility and the oppressive role of silent complicity. These images do not seek a clear moral, they show conditions. Sexuality also plays a central, albeit ambivalently fractured, role in the series. In the works of the Geil series or in the image Sex Master, natural motifs – blood-red mountain streams, darkening skies – encounter a language of exaggeration that hovers between self-parody and tragic self-representation. Here, sexuality does not appear as a lustful expression of the body, but as a projection surface for loss of reality, power fantasies and socially formed states of overload. The irony of Sex Master targets a social obsession with performance and comparative thinking. The supposed intimacy becomes a spectacle that, in its linguistic and visual exaggeration, empties the act itself – or, as the artist puts it: "Sex Master takes away the essence of sex."

The exhibition therefore focuses on the human condition – not idealised, but in all its contradictions. Like Eiler's previous figurative works, Bored to be alive does not treat togetherness as a romantic utopia, but as a fragile reality. Interpersonal relationships appear as experimental arrangements in which intimacy, aggression, indifference and longing are inextricably interwoven. The pitfalls of being together – whether in the family, among friends or in the social fabric – manifest themselves in images that simultaneously assert closeness and make distance substantial. The common ground is not romanticised but dissected.

Thus, the social sphere is portrayed not as a place of security, but as a field of ambivalent dynamics – deeply human, full of fractures. What is revealed in Bored to be alive is an artistic approach to the contradiction between longing and revulsion, between escape and powerlessness. Nature becomes a projection screen for an inner turmoil that is as individual as it is social. 'Home decoration' as a conceptual corset – and as a way of smuggling real feelings in through the back door.

"It's okay to cry again," says the artist. These works do just that – and allow viewers to do the same.